BACKGROUND OF THE HIGHEST COURT IN SERBIA

The Supreme Court of Serbia was established on September 9, 1846 (Old Calendar), on the basis of the Decree of Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević.

This brief overview of the 160 years of the history of the Court was based on the monograph "The Supreme Court of Serbia - 160 Years of the Rule of Law," by Nikola Žutić, PhD, scientific advisor at the Institute for Contemporary History in Belgrade (published by the Supreme Court of Serbia).

- Establishment of the Supreme Court of Serbia

- The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

- Courts during and immediately after the Second World War

The organization of the courts until the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia from 1992

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The first Constitution of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the St. Vitus Day Constitution from 1921, stipulates the introduction of a uniform legal system, that is, the equalization of the legal systems of the countries that made up the Kingdom. The Constitution prescribed the formation of a single Court of Cassation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, with a seat in Zagreb, the main task of which was to take care of the ‘proper and uniform application’ of` both substantive and procedural criminal laws, and introduce elements of continuity and consistency into the interpretation of the law so as to completely prevent legal inconsistency in jurisprudence.

At that time there was a so-called governmental-legal provisory with six inherited jurisdictions: Slovenia and Dalmatia, Croatia and Slavonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Vojvodina, where the power of cassation was exercised by: the Cassation Court in Belgrade, the Supreme Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Sarajevo), the Table of Seven in Zagreb, the Great Court in Podgorica and the Department of the Court of Cassation in Novi Sad (for the region of Banat, Bačka and Baranja) founded on September 17, 1920.

At that time there was a so-called governmental-legal provisory with six inherited jurisdictions: Slovenia and Dalmatia, Croatia and Slavonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Vojvodina, where the power of cassation was exercised by: the Cassation Court in Belgrade, the Supreme Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Sarajevo), the Table of Seven in Zagreb, the Great Court in Podgorica and the Department of the Court of Cassation in Novi Sad (for the region of Banat, Bačka and Baranja) founded on September 17, 1920.

All of the above courts have continued to work following the adoption of the St. Vitus Day Constitution, even though they should have been abolished when the Kingdom’s Court of Cassation in Zagreb was established.

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Serbia from June 1903 was also introduced in the annexed districts in Old Serbia (Kosmet) and South Serbia (Macedonia).

* * *

The Court of Cassation in Belgrade continued to operate, with jurisdiction over all the courts of first instance in the Kingdom of Serbia, the District Courts and Judicial Tables in Banat, Bačka and Baranja, over the Appellate Courts of Belgrade, Novi Sad and Skopje, while also exercising the main control over the disputes involving state accounts and performing control of the state.

After the amendments from 1922, the Court of Cassation in Belgrade with its Department B in Novi Sad had 35 judges, including: the Court President, his Deputy and four Presidents of the court departments.

* * *

The Department B of the Court of Cassation, with a seat in Novi Sad, was responsible for Banat, Baranja and Bačka. It had five judges, and the oldest of them managed the Department and was Vice President of the Court of Cassation. The judges were appointed by the King, at the proposal of the Minister of Justice. The Department began to truly operate in 1921. The first President of this Department was Jovan Lalošević, PhD from Sombor, followed by Aleksandar Dimitrijević, Sava Putnik, PhD, Jovan Savković, etc. In 1930 the Department was to be moved in Sombor, but the law which stipulated this - although it "came to life and and gained the obligatory force" - was not implemented in this regard and the seat of the Department remained in Novi Sad.

* * *

Although the courts were independent, there were still frequent and serious attempts to undermine this principle, but there was also courage and a clear decision of judges not to permit this. For example: in 1919, on a proposal from the Ministerial Council, the King issued a decree changing the existing Law on the Courts from 1865. The first judge of the Court of Cassation in Belgrade and its then President, the distinguished lawyer Mihajlo P. Jovanović reacted sharply to this illegal attempt of the administrative power to amend a higher level legal act with a lower level one - all this, of course, happening without the participation of the legislative power. He wrote a letter to then Minister of Justice Timotijević, which stated:

"The Court of Cassation is placed in a position where regulations contained in a decree should be applied contrary to those contained in a law. The Court of Cassation, of course, will not be able to do this. The Court of Cassation, working in its Session of all Judges, cannot confirm the legality of its actions referring to a Decree in matters in which there exists a Law. "

* * *

In January 1924, a magazine titled "Monthly Review of Legislation, Judiciary and Administration" was established, serving to publish court decisions brought in accordance with "civil, commercial and administrative justice". This is probably the forerunner of today's Court Practice Bulletin issued by the Law on the Organization of Courts from 1928, which was in procedure since 1823, also failed to lead to the establishment of the Court of Cassation in Zagreb. Until the end of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes this remained a utopian idea that has not been achieved.

* * *

The Law on the Organization of Courts from 1928, which was in procedure since 1823 also failed to lead to the establishment of the Court of Cassation in Zagreb. Until the end of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, this remained a utopian idea that was never achieved.

Federalism in the judiciary created many problems in practice, e.g. in the enforcement of court decisions - seeing themselves as a separate jurisdiction, Croatia and Slavonia did not enforce the decisions of the courts from Serbia. Yet another absurd lies in the fact that federalism did not bring unity, but instead emphasized the differences in the legal systems of the territories that were most evident in the extremely numerous cases of conflict of jurisdiction.

* * *

At the time of the so-called “Sixth of January Dictatorship”, the efforts regarding the harmonization of different legislations in the Kingdom continued. The Supreme Legislative Council, established at the Ministry of Justice in 1929, managed to harmonize the substantive and procedural criminal law, as well as civil procedural law. The uniform Criminal Code of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was passed, as well as the Law on the Bar, the Law on Enforcement and Security, the Law on Detention, as well as many others. Approximately 200 laws were passed just in 1929.

* * *

The State Court for the Protection of the State was established in 1929 as a division of the Court of Cassation in Belgrade, for the purpose of protection of the public order and public safety. The State Prosecutor was appointed as well. The cases involved mainly insults to the King or the royal family, activities against the state and the like. As there was no legal remedy against its decision, this Court became the highest level court in the country. It operated in panels composed of seven judges. Members of the Court were appointed by the King, at the proposal of the Minister of Justice.

This court later became independent. Curiously, the Law on the State Court stipulated a retroactive effect; it could therefore be applied to the situations that occurred prior to its adoption. Many esteemed lawyers pronounced it a very reactionary legislative solution, but this did not prevent King Alexander from passing two other laws with similar content. In a positive legal system, retroactive effect of legislation is absolutely unthinkable.

The elite judges of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia emphasized that true judicial independence does not exist if there is no independence from the environment in which one lives, and from the citizens of the community in which one lives. In order to preserve the independence from the environment in which he lived, a judge had to take care of his qualifications, of maintaining a certain standard of living that fit the judicial position and the excellent reputation granted to judicial authorities which he had to protect. A judge had to adjust his demeanor and activities to provide his environment and the citizens – litigants – with the impression that he is a free, independent and autonomous judge.

* * *

In 1938 the Ministry of Justice attempted to centralize the judiciaries of Vojvodina and Serbia by issuing a decree according to which the Department B of the Belgrade Cassation Court, located in Novi Sad, was to be transferred to Belgrade. However, the Novi Sad Bar Association, which called Department B the Court of Cassation of Novi Sad (the “Vojvodina Court of Cassation”) was expressly against such intentions of the Ministry of Justice.

The administrative authorities never wanted to pass the Law on Judges because they were never partial to the permanence of judicial office and the independence of judges; it always aspired to keep the judges, as well as other civil servants, as dependent as possible in order to exercise influence over them.

For example: the Law on Judges from 1929 abolished the permanence of judicial office. The judges did not raise their voice against this infringement, feeling that it was dictated by ‘higher reasons of the state’, and reasonably hoping that the transfers of judges would be performed only where absolutely necessary. However, the administrative authority took advantage of the situation and began to behave arbitrarily towards the judges, making unreasonable transfers and causing great harm to the judiciary. Daily newspapers often reported about the judges being moved from one end of the state to another ‘because the profession required it’ – even though there was no real need for such actions. The reason for this type of behavior of the administrative power was its need to intimidate the judges and thus break all resistance that could arise against the violation of the law by the administrative authorities.

The courts during and immediately after the World War II

During the war, of the Communist leadership authority imposed the People's Liberation Committees as the main authorities of the "power of the people." Committee for the judiciary of the People's Liberation Committee requested the separation of judicial and executive powers and the autonomy and independence of the courts: “For their decisions, the courts do not answer neither to the PLCs nor the Assembly (Plenary). They are obliged to rule lawfully”.

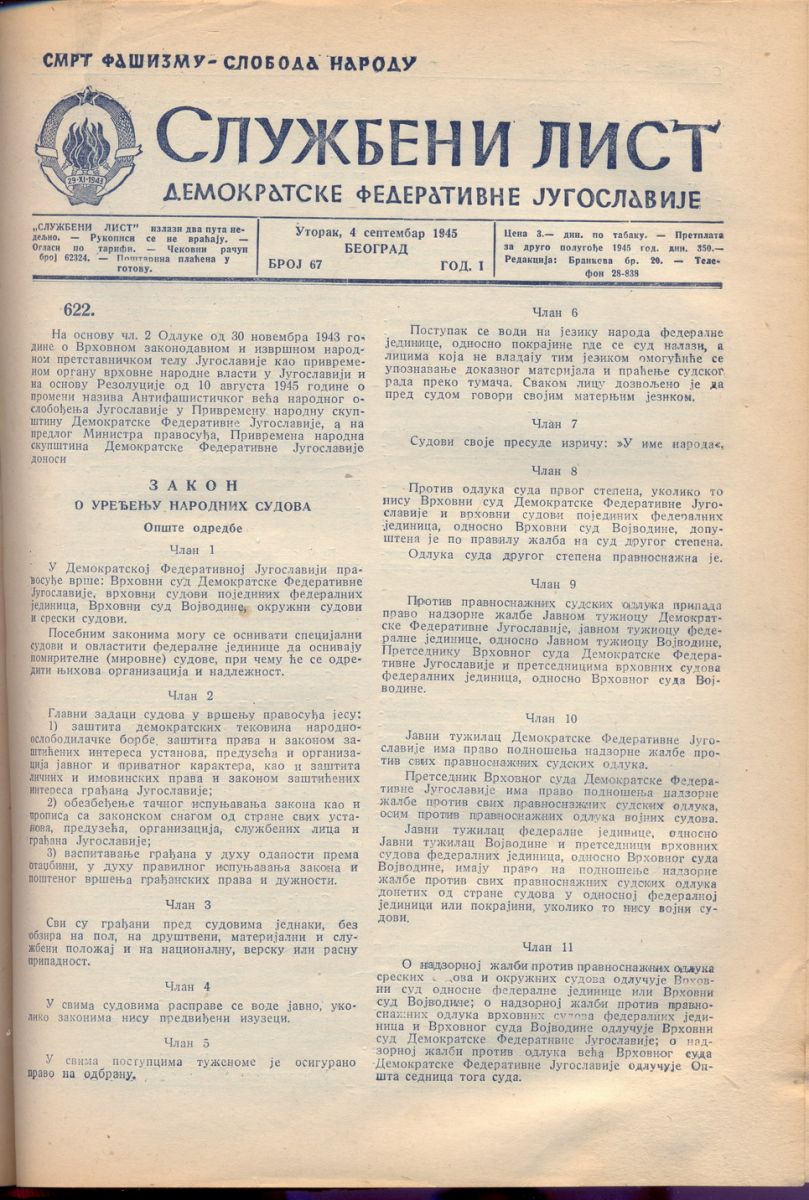

The Law on Organization of People's Courts was passed on 26 August 1945.

The principle of federalism as "a state-legal expression of equality of our people," has come to the fore in the judiciary through fact that the Supreme Courts of the people's republics became the highest judicial authorities in the republics, and they typically finally resolved all the civil disputes and criminal cases regarding the regular complaints and requests for the protection of legality, while in regard to the application of republican laws they ruled finally and exclusively.

The principle of federalism as "a state-legal expression of equality of our people," has come to the fore in the judiciary through fact that the Supreme Courts of the people's republics became the highest judicial authorities in the republics, and they typically finally resolved all the civil disputes and criminal cases regarding the regular complaints and requests for the protection of legality, while in regard to the application of republican laws they ruled finally and exclusively.

* * *

The new organization of the people’s courts in Communist Yugoslavia also allowed the participation of "non-lawyers" as members of the court, so that the truth would be determined and the cases in the people's courts resolved in the spirit of "the people's perception of justice."

The Instruction on the court procedures from December 1944 paints an idyllic conciliatory image of "brotherly" relations between the courts and the people: "Judges and court staff should be in contact with the people in order to teach them to live in love and harmony with each other, to help each other as much as possible, and not to offend anyone or cause anyone harm, because such actions will be strictly suppressed. In this spirit, as national institutions the courts will always endeavor, wherever litigation appears, to treat the parties as equally as possible”.

* * *

The courts are independent, they take decisions freely and independently of all other organs of the people's power, and they exercise judicial power in the name of the people. The people elect the judges, control them and can dismiss them if their work comes in conflict with the basic principles of the people's government and the legality of the national judiciary.

* * *

The judicial power in the territory of Serbia is exercised by the following people's courts: the municipal courts, the district courts and the ASNOS court (the Court of Cassation, the National Court of Serbia, the Supreme Court of Serbia) or the Supreme People's Court.

THE OATH: "I swear on the honor of my people that I will faithfully serve the people and that I will rule lawfully and impartially, protecting and defending the heritage of the people's struggle for liberation."

The laws and legal norms of the old, "decadent" civil judicial authorities were supposed to be rejected: "In a trial old legal norms shall not apply; instead, what should be sought is justice that is accessible to everyone ". This meant that old regulations were not to be applied and that new ones were to be be passed.

* * *

On 3 February 1945, the Presidency of AVNOJ passed the decision on the establishment of the Supreme Court of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, with a seat in Belgrade.

The Supreme Court of the Federal Republic of Serbia, with a seat in Belgrade, was established for the territory of the Federal Republic of Serbia as the highest judicial body. The court ruled and served as a court of cassation.

The Supreme Court of the Federal Republic of Serbia had a President, 14 judges, the required number of people’s judges (lay judges), a Secretary and other court staff. At the proposal of the of Justice Committee, the Court President and judges were appointed by the Presidency of ASNOS from among the graduated lawyers - honest, upright people who were dedicated to the national liberation movement.

The Supreme Court had criminal and civil panels, as well as a disciplinary panel. As a rule, President of the Supreme Court presided over one of these panels, and the rest were presided over by judges, in accordance with a schedule determined by the President. Also as a rule, the Supreme Court tried and decided cases in panels of three judges, in closed sessions and by majority vote.

The new Law on Organization of the People's Courts from 26 August 1945 stipulated that the courts were free and independent in their ruling, and that the limits of their actions were determined only by law. The control of the people was reflected in the public nature of the court hearings, the control performed by the people’s representative offices to which the courts were obligated to periodically submit reports on their work, the control that superior courts exercised over the work of the lower courts, etc.

The organization of the courts until the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia from 1992

The Law of 1945 established the area (kotar) and district courts, the Supreme Courts of the People’s Republics, the Supreme Court of the Autonomous Province Vojvodina and the Supreme Court of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia as the highest body of the judiciary in the FPRY.

From then until 1955 the organizational structure of the national courts did not significantly change. Their jurisdictions, composition and the mode of operation did, however, change from time to time.

* * *

The Criminal Procedure Code from 1953 envisaged certain cases where the Supreme Courts ruled in the third instance. In fact, these courts also ruled in the third instance in cases when they were deciding on the requests for protection of legality filed against the final rulings of second instance courts. The Supreme Courts ewere allowed to delegate their powers and had devolution rights in all the pending cases.

A significant act which reinforced the legality of the state administration is the Law on Administrative Disputes from 23 April 1952 which placed the control of legality of administrative acts was placed under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

* * *

The Constitutional Law from 1953 did not deal to a great extent with the judiciary and the public prosecutors offices, but this does not mean that there were no novelties or changes. The highest court in the country was renamed the Federal Supreme Court; the jurisdiction of the Federal National Assembly was established over the appointment and dismissal of the judges of this court, as well as the sole competence of the Assembly for the legislation relating to judicial and administrative proceedings, the administrative disputes, the enforcement of sanctions and security measures, the organization of courts and arbitration, the Criminal Code, etc.

* * *

The Law on Courts, the Law on Commercial Courts and the Law on Military Courts were passed in 1954.

Regular courts of general jurisdiction (area, district and supreme courts) had jurisdiction over all the criminal and civil cases as well as administrative disputes that did not fall under the jurisdiction of commercial and military courts. Commercial and military acted only in certain types of disputes and involving certain persons.

* * *

Although – even with considerable decentralization – a significant number of appeals and administrative disputes remained under their jurisdiction of the courts of the Republics, work in these courts, including the Serbian Supreme Court, was still carried out in panels within various court departments – criminal department, property and status department, commercial department, and the department for administrative disputes.

* * *

The Constitution from 1963 paid more attention to the judiciary than the earlier Constitutions, but failed to introduce any bigger changes. However, the Constitution maintained a form of judiciary that matched the earlier "statist" federal model. The specificity of this Constitution was that it introduced the control of constitutionality and legality as a constitutional function, entrusting it to the constitutional judiciary. It abolished in the Supreme Court of the Autonomous Province Vojvodina, and established departments of the Supreme Court for Vojvodina and Kosovo and Metohija.

* * *

Amendments from 1968 emphasized once again the importance of the legislation of the Republic and the autonomous provinces in which the Supreme Courts of Vojvodina and Kosovo were re-constituted. The term Kosmet, used for the region of Kosovo and Metohija, does not appear until the Constitution of 1992.

Amendments from 1971 introduced the "republican character of the judiciary i.e. the further decentralization of competences in the legislative area and the judiciary. The judiciary was regulated by the republics and provinces, in their own regulations. This is how a single judicial system came to exist.

* * *

The Constitution from 1974 established certain important principles of the judiciary: the constitutional principle of judicial independence, the principle of legality, the federal principle, the obligation of monitoring and analyzing social relations and phenomena, the constitutional principle of transparency, the principle of group decision - collegiality, the principle of participation of workers and citizens in trials, the principle of election, the principle of judicial immunity, the principle of special ethics of the judicial profession, the principle of two instances, the principle of exclusive competence of the judiciary, the principle of relevance and enforceability of court decisions, the principle of equality of the citizens before the law, the principle of free use of own language and script, etc. These and other constitutional provisions and principles were consistently elaborated in relevant statutory and other regulations.